What Were Group B Rally Cars?

- Homologation rules: required manufacturers to build only 200 road-going versions of their rally cars. No mass production required. Engineers could dream big.

- Minimal limits: Huge turbos, all-wheel drive, lightweight composites, and futuristic aerodynamics. All were fair game..

- And the arms race as a result. Within just a few years, cars doubled their power output, pushing well past 500 horsepower.

Why Group B Rally Cars Were Different

How Group B Rally Cars Changed Car Development

All-Wheel Drive Became Mainstream:

Audi Quattro’s dominance with AWD on snow, gravel, and mixed surfaces proved to the world that four-wheel drive meant faster. Soon, road cars from Subaru, Mitsubishi, and even Lancia followed suit, bringing AWD to everything from family sedans to hot hatches.

Turbocharging Revolution

Although the Renault 5 Turbo was the first, it was the Group B cars, such as the Peugeot 205 T16 and the Lancia Delta S4, that took turbocharging to the next level. They showed how small engines could make massive power with a boost. Thanks to rallying, the world saw turbocharged icons — the Ford Sierra RS Cosworth, Toyota Celica GT-Four, and later Subaru Impreza WRX. All owe part of their DNA to Group B.

Lightweight Materials

At speeds this high, weight was the enemy. Group B cars pioneered the use of Kevlar, fiberglass, and advanced composites. Materials quickly transferred from rallying into sports cars and supercars. So, what started as a rally experiment became standard practice for performance engineering in the late ’80s and ’90s.

The Homologation Effect

Group B’s 200-car homologation rule forced manufacturers to build road-legal versions of their rally monsters. That number was a golden mean: high enough to try radical design, low enough to keep the special sense. Cars like the Peugeot 205 T16, Lancia 037, and Ford RS200 gave ordinary enthusiasts a taste of rally technology. They instantly became collectibles, making non-fans stare and driving fans wild.

The Icons of Group B

- Audi Quattro S1 E2 – made AWD rallying standard.

- Lancia Delta S4 – twin-charged insanity: turbo plus supercharger.

- Peugeot 205 T16 – the most successful Group B car, with back-to-back titles.

- Talbot Samba Rallye (Group B version) — closer to the everyday fan, but still part of the family.

- MG Metro 6R4 & Ford RS200— outsiders turned cult heroes thanks to radical engineering.

Manufacturers from Europe to Japan poured money and talent into Group B. Every AWD, turbocharged hatchback you see today owes something to this era.

For all its brilliance, Group B carried a darker truth. The positive impact on automotive technology was huge, but so were the risks — risks no one wanted to fully admit until it was too late.

The Other Side: Why Were Group B Rally Cars Banned?

If I had to sum up why Group B ended, it would be in two words: out of control. Nobody — not the FIA, not the drivers, not the fans — was truly ready for what these cars unleashed. And it didn’t happen overnight. It was a step-by-step escalation.

The Start (1982)

The 1982 World Rally Championship was a whole other level of challenge. It was just the beginning, and Audi started. Its Quattro A1 dominated stages, showing what AWD and turbo power could do under the new Group B rules. Audi even won the Manufacturers’ Championship, while Michèle Mouton became the first woman to finish a season as WRC vice-champion, taking victories in Portugal, Greece, and Brazil.

What did people know before? Yes, Formula 1 had speed, but here were extremely powerful cars that looked like road cars — ripping through forests at 220 km/h (137 mph)!

Barely controllable, sliding between trees, with spectators pressed right up to the stage edges. The spectacle was intoxicating. The sport, which had been taboo before, now became normalized due to its popularity.

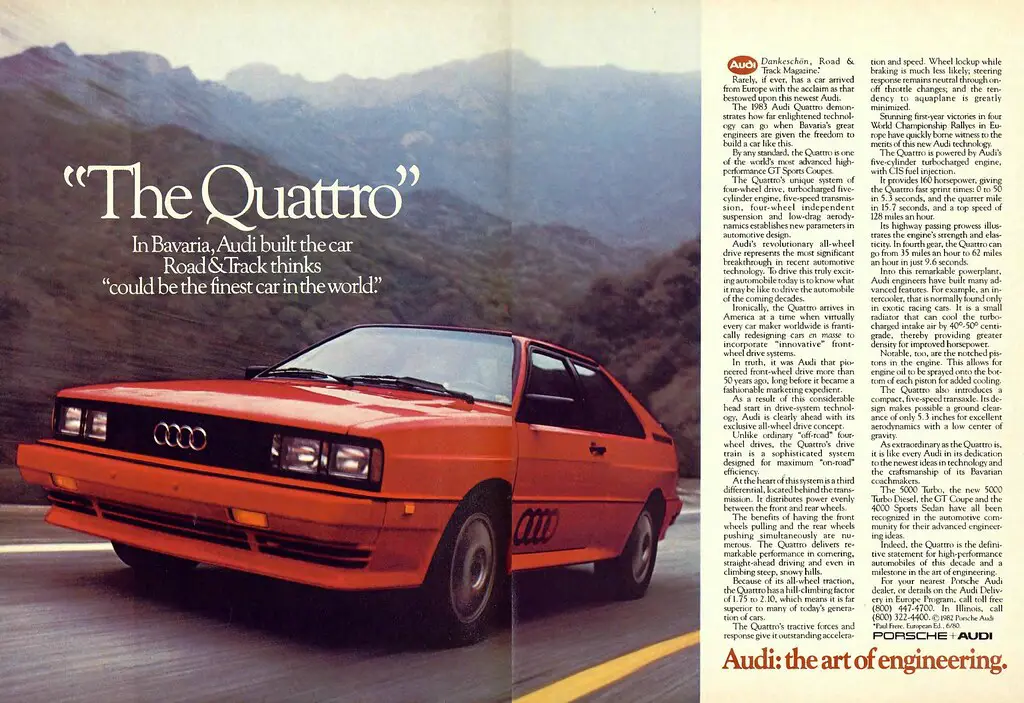

It started the marketing boost. Automakers quickly realized these rally monsters weren’t just competition cars — they were marketing weapons. The Quattro became a symbol, not only in motorsport circles but also in adverts and car magazines. They understood the crossover with the same tech appealed to a much wider audience.

A chain reaction (1983)

The 1983 WRC season just continued the trend. No strict limitations allowed Toyota and Lancia to fight back. A rear-wheel driven Toyota’s Celica Twin-Cam Turbo (TA64) became the “King of Africa,” tough enough to win endurance events like Safari and Ivory Coast, cementing the brand in rallying history. This car didn’t need the four-wheel drive to survive in the terrific deserts.

Lancia, meanwhile, unleashed the lightweight 037, a rear-wheel-drive machine that was as powerful but 200 kg lighter than Audi’s Quattro. Against all odds, the 037 won the 1983 Manufacturers’ Championship — the last RWD car ever to do so. To imagine how close the Lancia vs. Audi duel was, think that the count was just a point between.

Just look at how powerful Group B rally cars had become.

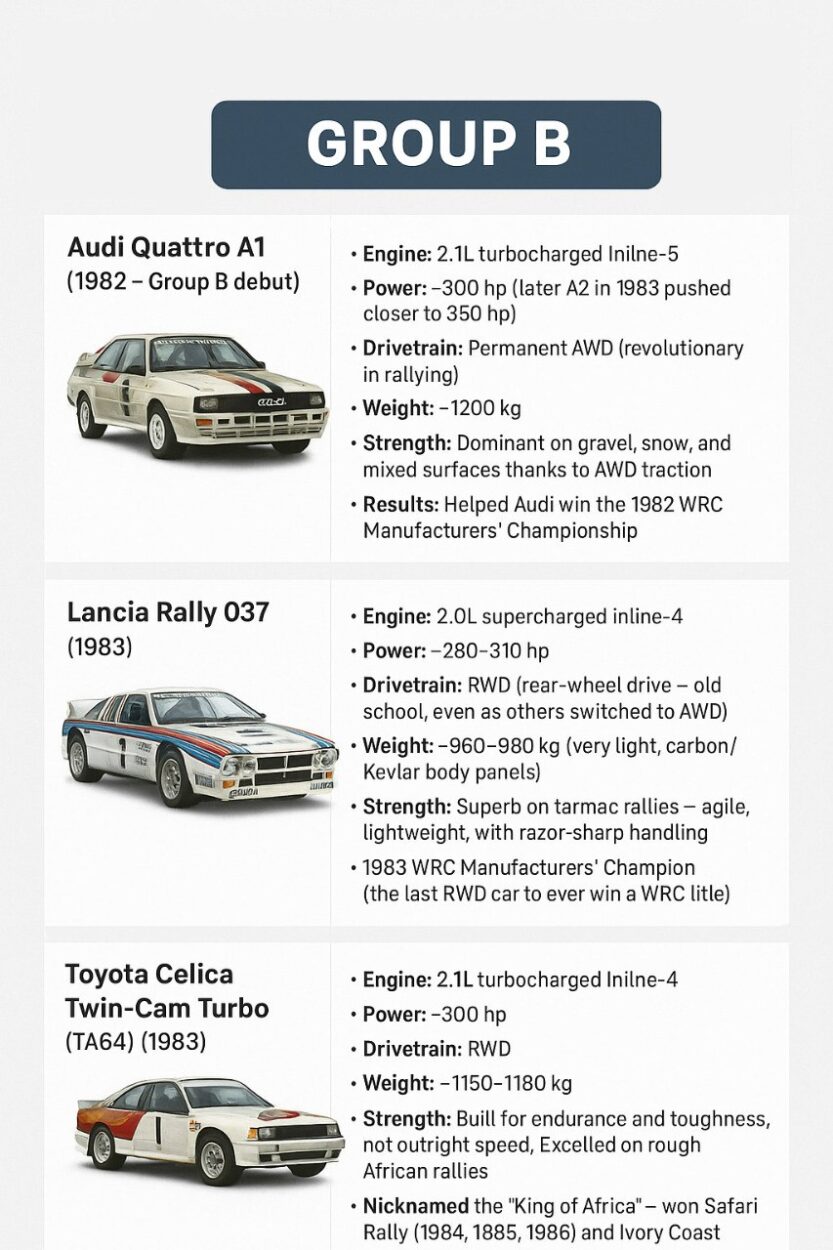

Car | Power | Drivetrain | Weight | Best Surface | Key Result |

Audi Quattro A1 (1982) | ~300 hp | AWD | ~1200 kg | Gravel, snow, mixed | 1982 WRC Manufacturers’ Champion |

Lancia Rally 037 (1983) | ~280–310 hp | RWD | ~960–980 kg | Tarmac | 1983 WRC Manufacturers’ Champion |

Toyota Celica TCT (1983) | ~300 hp | RWD | ~1150–1180 kg | Rough endurance | Safari & Ivory Coast rally wins |

It was like a chain reaction. With each passing season, the crowds grew. More fans, more risk-taking from crowds. Fans stood on crests and inside corners, inches from the racing line. Organizers couldn’t control the swelling numbers across 30 km of remote mountain stages. The warning signs were there — but nobody could slow the show down. Or, maybe they wouldn’t?

No turning back (1984)

Audi struck back in 1984, but then it came Peugeot. Peugeot’s homologated 205 T16 was compact, mid-engined, AWD, and … it made 350 hp from just 960 kg!

Any settings – welcome! Without exception, all-surface dominance with topping 210 – 215 km/h (130–133 mph). Ari Vatanen’s win that year proved that Peugeot was the new benchmark.

The 205 T16 changed everything. It went down in history not only as the car that led in 1985 and 1986, but also as the car that surpassed all that was possible. So, no wonder that it all ended with Peugeot.

It was clear: rallying had entered a new dimension with no turning back.

Thus, even in its first version, the 205 T16 could hit 100 km/h in around 5 seconds on gravel — numbers that no rally car had ever touched. Rallying at that speed, no one can guarantee that someone could avoid the tragedy.

As in earlier times, rallies always had crowds. People had become accustomed to danger, so it didn’t seem extreme. However, previous Groups weren’t as fast. On the other hand, localized events meant that near misses didn’t receive significant media coverage, even though drivers often reported narrow escapes.

However, as crowd sizes increased, like in Portugal, control broke down. People wanted to see what might happen, and it didn’t take too long.

Here’s the detailed rally cars explanation for new fans.

Just compare Group B’s Lancia and Peugeot with just a year of difference!

Spec | Lancia Rally 037 (1983) | Peugeot 205 T16 (1984) |

Engine | 2.0L supercharged I4 | 1.8L turbocharged I4 |

Power | ~280–310 hp | ~350 hp |

Layout | Mid-engine, RWD | Mid-engine, AWD |

Weight | ~960–980 kg | ~960 kg |

Strength | Tarmac agility, lightweight | All-surface dominance, development potential |

Weakness | No AWD, limited power ceiling | Turbo lag (early models) |

The Superiority (1985)

Peugeot evolved the 205 T16 into the Evolution 2 by 1985. In less than a year, 205 T16 had bigger wings, better brakes, and crucially, more power: now 450 hp in just 930 kg. With short gearing, it could go around 210–220 km/h and launch to 100 km/h in around 3 seconds — faster than Formula 1 cars of the day!

Rallying wasn’t just racing anymore. It was a race of superiority. Millions of fans packed into forests, fields, and mountain roads to watch these monsters fly by. But the safety rules hadn’t caught up. Drivers complained about uncontrolled crowds, stage layouts, and terrifying speeds. Manufacturers began refusing entries or stages, citing safety concerns. Organizers ignored it. The problem was evident, but who cared when the popularity of the WRC was booming and almost rivaled that of Formula 1? Instead, they chose a direction in which danger became an integral part.

Spec | Lancia 037 (1984) | Peugeot 205 T16 Evo 1 (1985) |

Engine | 2.1L supercharged I4 | 1.8L turbocharged I4 |

Power | ~325 hp | ~430–450 hp |

Drivetrain | RWD | AWD |

Weight | ~960–980 kg | ~910–930 kg |

Strength | Tarmac agility | All-surface dominance |

Weakness | No AWD, limited power | Turbo lag |

Results | Competitive only on tarmac | 1985 Drivers’ + Manufacturers’ Champion |

The First Incident (1985, Corsica)

And then it started the 1985 Rally Tour de Corse. Attilio Bettega lost control of his Lancia 037 and crashed into a tree. He was killed instantly.

In hindsight, it was the first clear sign that Group B had gone too far, but it wasn’t so evident at that time. Many dismissed it as a racing accident — the kind of risk drivers accepted. People getting used to the risk, no one asked or minded, “That’s too dangerous!” Nobody wanted to believe it yet.

Uncontrolled: The Price of Superiority (1986)

Right up until the end, there was hope that the next season’s cars would somehow become safer, more controllable, but it was false. The more power Group B cars gained, the more uncontrollable they became.

By 1986, the speed demons had reached their absolute peak. Think Group B’s Peugeot 205 T16 Evo 2, Lancia Delta S4, Audi Sport Quattro S1 E2, and Ford RS200 Evo were producing 450–550 hp, with some test engines rumored to break 600 hp! For context, a 2025 Formula 1 car produces around 850 hp — but runs on smooth circuits with full barriers.

Group B cars weighed under 1,000 kg, had no electronic safety systems, and were launched down narrow gravel tracks lined with thousands of spectators. The result? 0–100 km/h in under 3 seconds on gravel. The tragedy was just a matter of time.

The Results

Rally de Portugal (1986)

Joaquim Santos lost control of his Ford RS200 and plowed into a crowd,injuring dozens of spectators. Leading drivers immediately withdrew, declaring that crowd safety was impossible under current conditions. For the first time, it wasn’t just about driver risk — the fans were under fire too.

Tour de Corse, Corsica (May 1986)

A few months later, the championship leader Henri Toivonen and co-driver Sergio Cresto crashed their Lancia Delta S4 into a ravine. The car exploded in flames, killing both instantly. This was the tipping point. If even the most talented driver in the fastest car couldn’t survive, the problem was bigger than skill.

As for the drivers, Walter Röhrl, Michèle Mouton, Juha Kankkunen, Stig Blomqvist, and Henri Toivonen became legends. Drivers who could handle — and even win with — the Group B rally car were considered to have natural rallying skills. Read the difference in driving feel at the wheel of Group B and current rally cars at WRCWings, but we are moving forward.

The 1986 “Monsters” at a Glance

- Peugeot 205 T16 Evo 2: 450+ hp, AWD, ~0–100 in 3s.

- Lancia Delta S4: 480–550 hp, AWD, 0–100 in ~2.6s, top >250 km/h.

- Audi Sport Quattro S1 E2: 500+ hp, AWD, 0–100 in ~3s, wild aero.

- Ford RS200 Evo (works spec): ~500–600 hp, AWD, some testing versions exceeded 350 km/h (!) in straight-line speed records.

Group B was the most powerful rally cars ever built. And on the very next day after Corsica’s tragedy, FISA (FIA now) president Jean-Marie Balestre made a point. FIA banned all the Group B rally cars at the end of the season forever.

The Destruction:

This time, motorsport safety issues were a headache for the FIA. Besides the WRC, there were many questions for Jean-Marie Balestre to answer. But the ‘Group B issue’ was an impossible dilemma.

What were the options? They could add stricter limits to Group B, but Group A and N already existed as “slower” categories.

They could try to improve event safety for the following rallies, but controlling tens of kilometers of open roads filled with spectators would have required massive resources they didn’t have: money and people.

It also wasn’t possible to rewrite the FIA rules because the bureaucracy moved too slowly.

Instead, the FIA fell into its own trap. Resolving the future of the rally sport required an innovative approach. On the one hand, they needed for safe cars and events, but these cars also had to be as fast and thrilling on the other hand. And that was a dead end. Losing everything they had made by 1986 meant the biggest defeat, emphasizing the insolvency of the FIA.

In hindsight, the decision was both obvious and challenging. Innovations in safety were needed, such as the HANS device and electronic safety systems inside cars, which motorsports gained in the 2000s and 2010s. However, developing all of these took many years.

At that time, however, a quick decision was needed, so they chose destruction. Rallying had become so popular and dangerous that it could not be slowed down without dismantling it.

The Cancelled Future

They wanted to preserve the technologies and developments that produced speed and excitement. Therefore, the FIA briefly proposed Group S as a replacement for Group B. The main idea was to keep prototype freedom, but cap power at ~300 hp. They thought ‘Okay, that will be a ‘prototype’ category, still spectacular, but it will be safer!” It was like chasing two rabbits at once, so no wonder they didn’t succeed.

Manufacturers, such as Peugeot, Lancia, Toyota, Audi, and Ford, already had prototypes in development. However, the idea died before it began, and their developments remained prototypes forever.

Instead, Group A was elevated to the top class in 1987. And someone adapted pretty fast. Lancia adapted instantly, launching the Delta HF 4WD, which began its legendary run of six straight championships.

Toyota, Ford, and Mazda survived. But others couldn’t: Audi withdrew after 1986, Peugeot pulled out, and started a new chapter with the 24 Hours of Le Mans, while Opel/Nissan faded away.

The Aftermath

Even for those who transitioned, the public love seemed to be missed forever. With Group B rally cars gone, they took the worldwide recognition. The spectacle, the insanity, the unfiltered danger — gone. Yet, rallying endured.

No one could have guessed that, ten years later, the WRC would find a second wind thanks to Group A cars like the Subaru Impreza and the Mitsubishi Lancer. And in 1997, the FIA introduced a brand new formula: the World Rally Car — a different kind of monster, and the rebirth of the WRC. That was definitely another story, though.

But Group B? That chapter closed forever in 1986, remembered as the wildest era of rallying.

Why Group B Rally Cars Felt So Fast

In two words: raw power. No traction control. No anti-lag (in the modern sense). There were no electronic safety nets, either. Just a screaming turbo, a set of wings that sometimes worked, and a driver with the skill — and courage — to keep it all on the road.

Manufacturers were chasing speed at any cost. The Lancia Delta S4 even combined turbocharging and supercharging — “twin-charging” — for brutal low-end punch and massive top-end power.

Engineers experimented with large wings, diffusers, and composite materials that resembled science projects more than road cars.

That’s why Group B cars feel so mythical today. But nostalgia often blurs the numbers. Are you sure they were really faster than the Rally1 cars you see in WRC now?

Group B vs Rally1: Which Is Faster?

Top Speed: Group B had the edge, especially on straightaways. The Audi Sport Quattro S1 E2 could top 220 km/h, while the Ford RS200 could over 250 km/h in testing. Rally1 cars (non-hybrid 2025) rarely exceed 210 km/h.

Acceleration: Even Group B rockets like the Peugeot 205 T16 Evo 2 can accelerate from 0 to 100 km/h (0 to 62 mph) in about 3.0 seconds on gravel. After flicking the hybrid, the Rally1 accelerates in ~3.5 seconds.

But here’s the truth. Rally1 is 10 km/h faster than Group B overall due to its dominance in average stage speed. This is thanks to its 400-horsepower engine and modern tools like aerodynamics, suspension, and tires.

Thus, the Toyota GR YARIS Rally1 2025 carves through twisty gravel and tarmac at an average speed of 129.9 km/h (Kalle Rovanperä’s Finland 2025 record), while Group B averaged closer to 110–115 km/h on similar stages.

So yes — on the straights, Group B was quicker. But in the real test of rallying — corners, chicanes, hairpins, and endurance — Rally1 cars are faster overall. Here are the Toyota GR YARIS Rally1 2025 specs.

The Trick Question

Group B was the golden era that finished so soon because the cars were ahead of their time. The technology, the danger, and the spectacle all collided in a way that could never last. Even if the group was never launched, I think there must still be someone to bring these cars into the championship. I’m not sure, but I think without Group B, the WRC might never have become the global phenomenon it is today. It gave a rallying of its original world championship spirit.

Group B has inspired not only fans but also those who rule this sport. So, the idea behind the Rally1 car was to capture the raw power of Group B while ensuring safety. Do they succeed? Partly.

Yes, Rally1 cars may be quicker through the stages, safer for drivers, and more consistent for teams, but the raw, unfiltered spectacle of Group B — flames, noise, danger, and sheer insanity — remains unmatched. That’s why, four decades later, fans still talk about Group B rally cars as the wildest machines ever to compete in the WRC.

Is it possible to reset Group B? Only time will tell, but once it’s done, the WRC will regain its golden status worldwide.